By Samantha Caputo | Mon, November 12, 18

“Put a price on carbon” is a phrase growing in popularity as policymakers, scientists, economists, and others continue to determine pathways to reduce carbon emissions. But, what does it mean to put a price on carbon and why should we consider this?

These are questions we have to answer in order to present the case for pricing carbon to state legislatures. To take a deeper dive on this topic, I recently attended an Environmental Business Council event on carbon pricing. Presenting the policy, economic, and technical perspectives, panelists provided a well-rounded explanation of effective carbon pricing schemes. Let’s take a look at the case for putting a price on carbon.

The true cost of carbon

Climate change is one of the biggest challenges we are facing, and depending on how we address this challenge, the impacts will affect generations to come. In order to avoid catastrophic weather events and permanent damage to the environment, we need to take action now.

According to the National Climate Assessment, climate change increases extreme weather, and extreme weather has a cost. As one example, flooding and wildfires lead to displacement, infrastructure failure, and health costs. If we consider the costs of extreme weather, we see the social cost of carbon. Yet, these costs are not included in the price of fossil fuels.

The price of fossil fuels reflects the private costs, not the social costs. Casey Pickett, Director of the Carbon Charge at Yale University, explained that without the social costs, society pays a lower price and customers overconsume. This results in higher emission levels. Markets are efficient when the price of goods reflect their true costs. In order to reflect the true cost of fossil fuels, a price on carbon is necessary in order to account for the social cost of carbon emissions.

Calculating the cost

A carbon tax or cap and trade are both schemes to drive reductions in emissions. Let’s take a closer look at each.

Under a carbon tax, everyone pays a tax on the fossil fuels they use based on the carbon content. Using this equation, the tax can be used to target a particular sector:

Tax base (what you tax, i.e. carbon) x tax rate (fee) = tax revenue

Professor Janet Milne of Vermont Law School used this equation to show that a jurisdiction may choose to phase-in a tax, starting with easy-to-reach sectors such as transportation, working towards more challenging sectors, like residential. Phasing-in a tax to cover all sectors of the economy provides each sector an adjustment period, as well as time to prepare before the tax becomes applicable.

Furthermore, an emissions assurance mechanism – such as the state’s emission reduction target – can be included in the law. This creates a metric to track progress towards a goal. Based on progress, this mechanism can also be used to determine the price on carbon.

When creating a new tax, it is important to consider how the revenue from the tax is used. There are two main avenues:

- Revenue neutral

- Tax monies are returned to consumers via rebates, therefore not growing the government

- In many states, revenue neutral isn’t considered an actual tax

- Revenue positive

- Tax monies can be used to create a government fund where the revenue is used for policies and programs aimed at reducing carbon emissions, working towards state policy goals.

- Under this pathway, policymakers should consider including provisions preventing the diversion of funds and guidelines for how the funding it used

Cap and trade is an alternative to carbon tax. This mechanism is put in place by government or regions to set an emissions cap. The trade factor comes into play during an auction where allowances of emissions up to a certain level are purchased and sold. Typically under a cap and trade policy, the cap on allowances shrinks over time.

Massachusetts Senator Michael Barrett spoke about the carbon pricing bill that was introduced in the Bay State during the 2018 legislative session. The senator explained that the bill would require the governor to design and implement a carbon pricing mechanism. This takes the weight off legislators to decide between revenue neutral or positive taxes, or a cap and trade program. The bill was written this way to prevent it from being too ambitious. Senator Barrett alluded to plans that will reintroduce the bill during the 2019 legislative session.

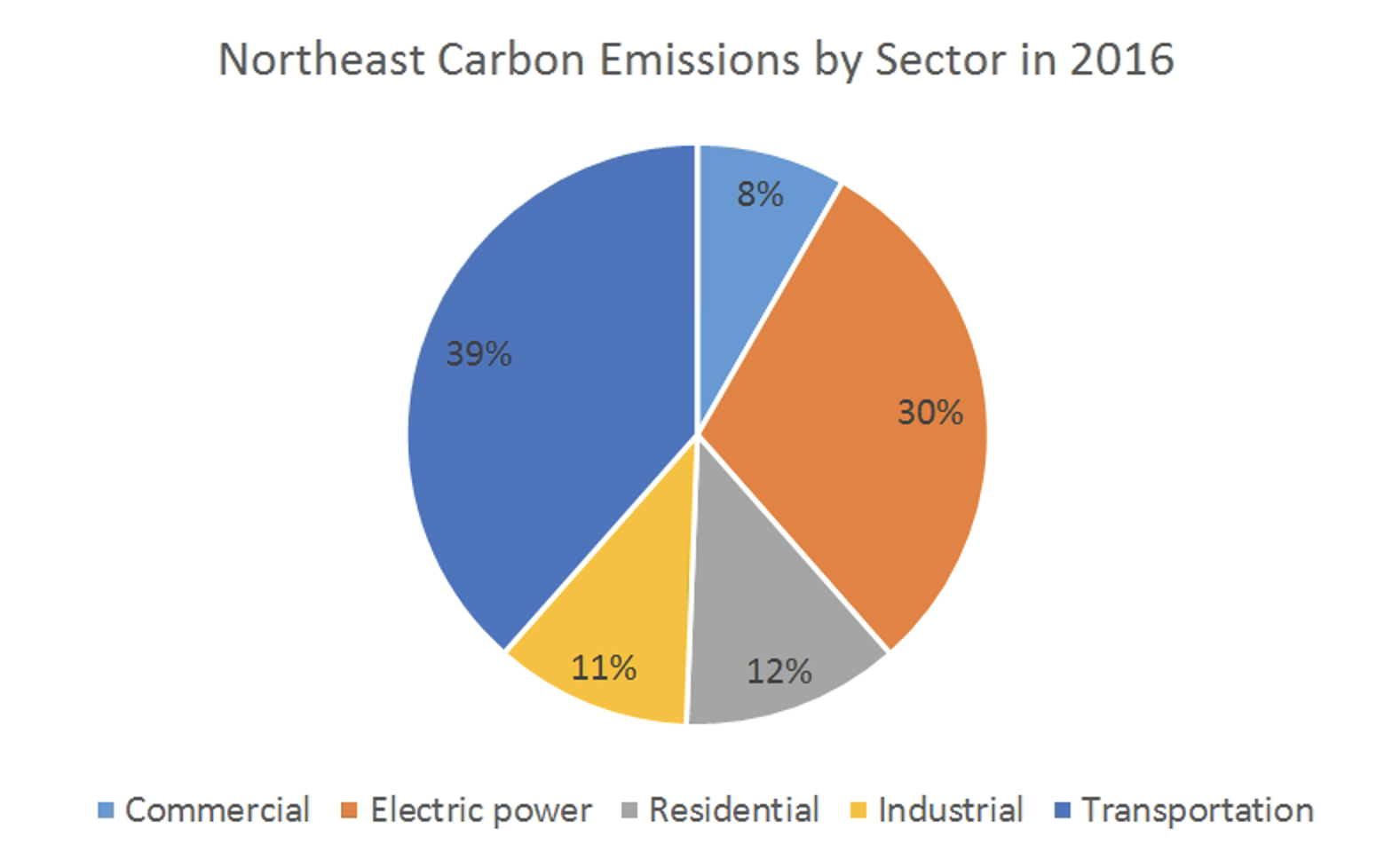

For both policy pathways, it is important to look beyond the electric power sector and target building and transportation decarbonization. According to U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), U.S. electric power sector carbon emissions have declined 28 percent since 2005 because of slower electricity demand growth and changes in the mix of fuels used to generate electricity. Yet, in order to achieve deep decarbonization, the building and transportation sectors – which account for a combined 69 percent of total emissions in the Northeast – need to be targeted.

Dan Dolan, President of New England Power Generators Association (NEPGA), highlighted the importance of reducing emissions from transportation and highlighted electrification as a means to do so. A price on carbon may drive consumers to alternative modes of transportation, such as electric vehicles.

Prep plans require funds

The impacts of climate change are already here, as evidenced by 2018 wildfires in California, Hurricane Florence, bomb cyclones in the Northeast in winter 2018, and the list goes on. In order to mitigate severe weather and ensure low-carbon, resilient places to live, work, and play we need to target buildings and transportation. Carbon pricing can help target these sectors and provide the much-needed funds to promote other policies and programs that support carbon reduction.

We are going to have to spend money on climate adaptation and mitigation. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) warns that the cost of climate adaptation in developing countries could rise between $280 and $500 billion by 2050 if the temperature exceeds two degrees Celsius. Carbon pricing provides a source of revenue to cut down future costs and mitigate rising temperatures.

According to the recent IPCC special report, we could hit the 1.5 degree Celsius mark between 2030 and 2060. If there is any chance to mitigate this global temperature increase, action needs to be taken now. Carbon pricing is a necessary part of a larger package of policies that can reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Now, put your hands up if you want to put a price on it!