By Anonymous (not verified) | Tue, July 12, 22

This blog was co-authored by Aditi Dalal, Public Policy Associate, and Erin Cosgrove, Public Policy Manager.

Welcome to the newest installment of a new blog series called Turning Policy into Performance. In this series, we'll take a look at how states can implement decarbonization and climate goals with energy efficiency programs.

Pricing carbon can account for the external costs of carbon emissions. External costs are the unaccounted price that the public pays for the impacts of emitting carbon, including damage to agriculture and healthcare costs when heat waves or droughts occur, as well as impacts of flooding from sea level rise. Putting a price on carbon internalizes those external costs and provides an economic signal to encourage utilities to design programs that reduce emissions. This price signal can also stimulate market innovation, fueling economic growth in clean energy technology.

For energy efficiency programs, pricing carbon in the cost benefit analysis better reflects the costs of climate impacts and encourages the implementation of program designs that reduce carbon emissions. This can align energy efficiency policy with state climate goals. States with aggressive carbon reduction goals may require a significant portion of electrification of end uses, such as replacement of oil or natural gas. These goals may seem costly if the price of carbon is omitted. Pricing carbon encourages energy efficiency that results in deeper savings, such as fuel switching and weatherization, by recognizing the economic benefits that comes from reducing carbon in the atmosphere.

How to Price Carbon?

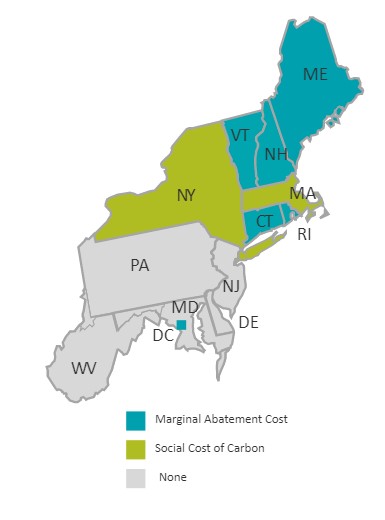

There are two ways to include the cost of carbon in cost-benefit analysis: the social cost of carbon or marginal abatement cost. Both of these will value the reduction of one ton of carbon dioxide, but marginal abatement derives the value from costs to the electrical grid while social cost of carbon derives the value based on economic and societal damages.

Marginal Abatement Cost or Avoided Cost of Compliance with State Climate Act

States are passing state-specific legislation with goals on climate reductions and energy efficiency measures. Energy efficiency reduces the costs to achieve climate goals because it reduces overall system demand, lowering the need for renewables and other clean energy technologies. Including the avoided cost of compliance will value the emissions reductions achieved through energy efficiency programs in line with state climate goals. For example, the 2021 Avoided Energy Supply Component Study calculated the New England-based marginal abatement costs by looking at the composition of the electric sector. This projection is based on the anticipated future costs of offshore wind energy, which results in $125 per short ton of carbon dioxide. If a state has more ambitious climate goals, such as 90 or 100 percent reductions by 2050, the price per ton increases to $493 based on future cost projections for renewable natural gas.

Social Cost of Carbon or Marginal Damages Approach

Social cost of carbon, or marginal damages approach, estimates the future environmental and social damages caused by a metric ton increase in carbon dioxide emissions in a given year. It also presents the economic benefit that results from reducing greenhouse gas emissions. To determine the social cost of carbon, a state would examine how energy efficiency can reduce carbon dioxide emissions and then estimate the damage and increase in climate change impacts that would result from not removing the emissions. These costs can result from changes in agriculture production, changes in health outcomes, sea level rise and property damage, changes in energy consumption, and declines in labor productivity.

Another factor in determining the social cost of carbon is the discount rate. A discount rate determines when and for how long the impacts of an investment will be seen. A higher discount rate reflects an investment that will provide short-term benefits (five to eight percent) while a lower discount rate reflects an investment that will provide the same or more benefits to future generations (negative percent to three percent). For example, a difference in a discount rate of two percent to one percent with the social cost of carbon will bring the price per ton from $119 to $394. This price difference can allow for programs that encourage fuel switching and prioritize strategic electrification, which may not show benefits for a few years, to pass the cost-benefit analysis.

Conclusion

Estimating the impact of energy efficiency on lowering emissions can help to align climate and energy efficiency policy. It is important that states start to account for these emissions and include them in the cost benefit analysis to encourage innovation in energy efficiency programs and align them better with state climate policy.