By Erin Cosgrove | Wed, September 22, 21

Welcome to the newest installment of a new blog series called Turning Policy into Performance. In this series, we'll take a look at how states can implement decarbonization and climate goals with energy efficiency programs.

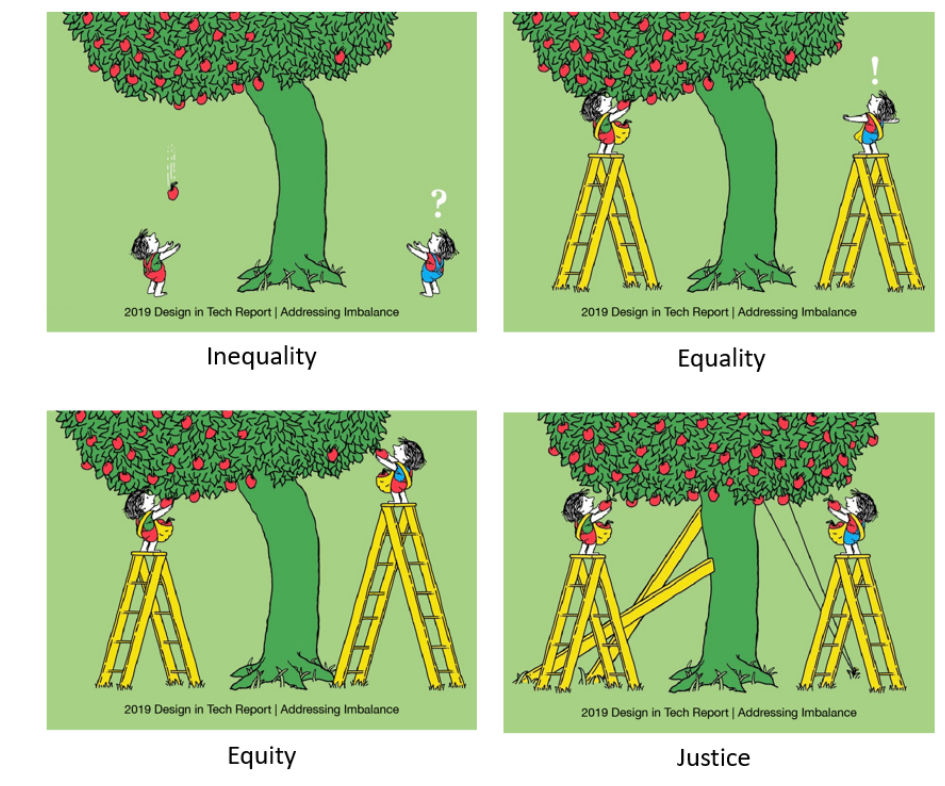

History shows that some energy practices can perpetuate inequity and create additional economic hardship for already overburdened communities. Embedding equity metrics in energy efficiency programs now provides opportunities to address systemic racial inequities in housing, energy, and environmental policy. By using data, policymakers and implementers can provide a baseline understanding of how inequities are embedded in current programs, provide accountability during program design, and ensure measurable, real achievement. By using data, policymakers and implementers can implement restorative justice.

Restorative justice, as defined by the Justice in 100 Metrics Report from the Initiative for Energy Justice, is “a holistic understanding of equity that recognizes past and current energy injustices should guide the implementation plans to advance energy justice and confer benefits to communities most burdened by these injustices. Restorative justice should underlie all aspects of the implementation process and in particular help frame, ground, and clarify the definitions and parameters of the process overall.”

This blog will outline three steps in the energy efficiency portfolio planning process (establishing goals, identifying inputs to the cost-benefit calculations, and tracking and reporting) and highlight metrics for restorative justice efforts in energy efficiency programs. These metrics can serve as equity indicators for implementers and policymakers, helping “to establish the state of equity at a given point in time, and are therefore effective tools for collecting baseline measurements and setting long- and short-term goals,” as recognized by the above-mentioned Justice in 100 metrics report.

Portfolio Goals That Prioritize Restorative Justice

Energy efficiency program goals represent what programs aim to achieve. Typically, goals focus on first-year or near-term energy savings because it’s easier to describe, measure, and plan programs in short cycles. But this way of identifying success is short sighted, and can perpetuate the institutional racism embedded in energy policies. Short-term goals encourage implementers to go to low hanging fruit like lighting rather than implementing programs with long-term meaningful benefits. Two ways to undo this bias in program design is to create a separate target for low-income programs or set goals based on benchmarks.

-

Low Income and Small Business Savings Targets: Current energy efficiency program goals usually focus on energy savings. While a savings target is valuable, it can sometimes lead administrators to overlook other important considerations – such as equity and accessibility – in delivering programs. Including a savings target that requires a portion of savings from environmental justice, moderate- and low-income, small business, and/or other areas identified by state policy will encourage program design to deliver to these areas, resulting in additional targeted resources that may have otherwise never existed.

-

Equity Benchmarks as Goals: Setting goals focused on accomplishing benchmarks instead of a number of savings is one way to redirect these programs to be innovative and accomplish policy goals. Policymakers can use state climate plans or other targets to identify an appropriate metric, such as implementing interim targets through energy efficiency plans to achieve a statewide goal of weatherizing homes. Alternatively, regulators could use participation goals to show community engagement and benefits. Another possibility could be a lower number of shutoffs or reduction of energy bills, indicating that programs have alleviated energy burden in the territory.

Cost-Benefit Tests That Account for Environmental and Societal Impacts

Cost-benefit tests are used to assess the cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency programs to ensure ratepayer investments result in ratepayer benefits. In most states, the cost-benefit analysis only includes the costs and benefits from the perspectives of the utility and program participant. But the energy system does not exist in a vacuum. How much power is used and how it is created impacts society and the environment around us. Therefore, it is paramount to address equity and embed restorative justice policy in cost-benefit analysis. Below are a few approaches that states can take to begin this process:

-

Equity specific metrics: Non-energy benefits account for external impacts of energy efficiency programs. For historically marginalized communities, these negative and positive impacts are often multiplied. Therefore, one way to design cost-benefit tests to better account for these impacts is by including additional benefits metrics that can account for these disproportionate impacts. Metrics implementers can use include: public health costs, improvements in indoor and outdoor air quality, local and state economic impacts, investment in homes, and improvement in health and comfort.

-

Equity adder: Utilizing an equity adder can quantify the disproportionate impacts and benefits felt by these communities without needing to identify precise numbers for each benefit. Vermont has adopted a 15 percent low-income adder, recognizing there are unaccounted for benefits to low-income programs, such as reducing energy burden, comfort from more controlled indoor climates, and investment in homes. For more information on how to include an equity adder in a state cost-benefit test and examples of what other states have done, see Non-Energy Impacts Approaches and Values: an Examination of the Northeast.

To see more about how to integrate new cost-benefit testing practices into your state, see NEEP’s implementation Guide on Establishing a Jurisdiction-Specific Cost-Benefit Test.

Tracking and Reporting Metrics That Provide Accountability

Similar to tracking and reporting carbon policy to achieve climate goals, tracking and reporting on equity policy can ensure that programs are successful and hold actors accountable when needed. Tracking can allow implementers and other stakeholders to find any gaps in real time. Further, displaying this information in a publicly-accessible database can create a better picture of the impact of these programs for utilities, regulators, and consumers. Below are three areas of metrics that can inform this process and help to achieve equity priorities.

-

Participation Metrics: Tracking metrics that show data about participants in a program can enable implementers to find any gaps in participation based on incentives, marketing, or other program design elements. For example, if a program is geared towards a certain type of home or income level, collecting data to identify who is likely to participate can verify if the intended consumer is receiving program benefits.

-

Location Metrics: A metric that indicates where program participation is occurring, such as participation by zip code, can show where programs are most successful reaching customers. Further, if other data can be used to compare participation, such as census tracts or other indicators, this metric can indicate which communities are more likely to participate in a program, allowing for replication.

-

Workforce Composition and Hiring Metrics: Underpinning all energy efficiency programs is a community of companies and workers who face numerous new opportunities as these programs grow. Without accountability, this workforce could perpetuate inequities as well. But metrics that track workforce growth and hiring practices can provide accountability and access to help undo these barriers. For example, public-facing reporting on transactions with women-owned or minority-owned businesses (WMBE) can encourage companies to expand their relationships with businesses. For more information on workforce best practices, see NEEP’s Equitable Workforce Best Practice Guidance.

Integrating equitable data and metrics into energy efficiency policy will provide insight into how programs are not working and hold the industry accountable to do better. Because data is able to break down policy decisions into numbers, it will hold programs and institutions accountable in ways that they have not been before. If we start now, policymakers and implementers can use these metrics to provide a baseline understanding of how inequities are embedded in current programs, provide accountability as programs are designed, ensure measurable, real achievement, and ensure that these inequities will not perpetuate further.