By Dave Hewitt | Sat, February 23, 19

What are the potential benefits of building decarb to low-income households?

For some, the key benefit might be a job. A second valuable benefit, also deeply associated with energy efficiency, will likely be greater health and comfort. A third important benefit, especially for those that heat with fuel oil and propane, will be lower energy bills. It might seem odd not to start with lower energy bills, but building decarbonization is a broad strategy and a big strategy, and getting maximum benefits to low-income households will require some specific choices in policies and programs.

In the Northeast U.S., the specific local economic benefits of building decarbonization strategies have not yet been analyzed, but any activity that uses local businesses rather that buying fossil fuels from another state or country clearly has home-grown benefits. Multiple studies have shown the job creation potential of renewable energy and energy efficiency, which are key elements of the decarbonization strategy. But decarbonization can offer even more installation and manufacturing jobs related to heat pumps, controls, and other newer technologies. It may even be possible to lead some building decarb efforts with low-income programs, as happened in Wisconsin during the 1980s when bringing high efficiency gas furnaces to scale. Contracts between utilities and vendors to install efficient gas furnaces in low-income housing created cost reductions and required better warranties, reducing barriers to all customers for a then-new technology.

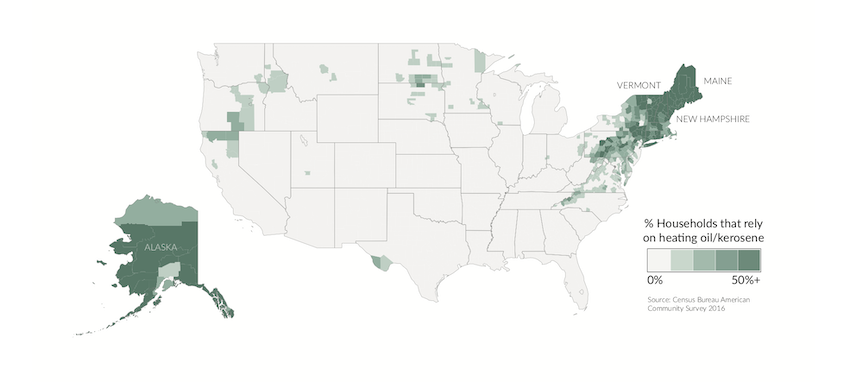

The Island Institute and the Maine Governor’s Energy Office recently published “Bridging the Rural Efficiency Gap” (http://www.islandinstitute.org/bridging-rural-efficiency-gap) which discusses the barriers and effective strategies to address high energy costs in rural, largely oil-dependent communities. The use of fuel oil for heating in America is shown in Figure 1, and the concentration of fuel oil space heating in the Northeast is remarkable. In Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire, some of the nation’s oldest housing stock is also a cause of high energy bills. It would be great to focus not just on efficiency in this housing, but on a complete modernization of the heating system in conjunction with deep efficiency and advanced controls.

Figure 1. Percent of households (by county) heating with oil and kerosene in the United States

Source: Census Bureau, American Community Survey (2016)

Rural communities face unique problems in terms of isolation, access to services, and business development. Decarbonization strategies may be able to build some home grown renewable resources and low-temperature heat from agriculture or small industries sources that heat pumps can use to create local renewable heat sources rather than burning fossil fuels.

In the Northeast, fuel oil is a major heating source in urban areas as well, frequently in lower-income areas of cities with older housing stock. As in some rural areas, older housing (possibly in poor repair), expensive heating fuel, and lower incomes create energy affordability issues while also contributing significant carbon and other pollutants into the environment.

Buildings as Communities; Buildings as Infrastructure

Decarbonization of buildings is a major shift in why and what is financed with public or utility dollars. There are innovative approaches and new business models that can be part of the solution. In some cases, we need to go bigger than a building – the typical customer – and go to community-scale solutions. When working with low-income households, we need to turn the major barriers of credit availability and split incentives (e.g. rental properties) into new community infrastructure and business models for providing heat.

Parts of our buildings could be treated more as infrastructure. A gas utility can rebuild gas lines to serve communities with long-term financing, depreciation schedules, and a financial return based on capital investment – tools certainly not available to low-income customers. Can a neighborhood install a heat pump system that shifts the near-term costs to a utility or public entity rather than a home or property owner? Can a utility sell heat rather than fuel? Well, it has been done.

Let’s Get Started

NEEP has drafted an initial three-year plan for starting building decarbonization in the Northeast. We plan to vet this draft regionally in 2019 and publish an improved version (while we are simultaneously working on the parts of the plan that already have financial support). The plan has three broad components – technology, consumers and policy and programs. NEEP is already deeply involved technologies such as cold climate air source heat pumps and residential controls , so let’s consider consumer issues and energy poverty.

NEEP recommends that the Northeast start with consumers who heat with fuel oil and propane, because these fuels are more expensive for consumers and the carbon savings potential is high. The Northeast is loaded with consumers, including many low-income consumers, who live in fuel oil-heated buildings that need attention. These efforts must specifically address low-income households that heat with fuel oil and propane, including rental properties, to reduce their energy burden.

NEEP’s draft strategy includes elements such as:

- Analyzing common housing stock in the Northeast to determine the best retrofit choices for space heating, water heating, efficiency and controls;

- Determining the costs and possible financial or new business models to provide the services;

- Working with advocates and service communities that are already engaged with low-income energy and housing issues to determine proper strategies; and

- Working with partners to develop policies and programs to secure needed investments in our building infrastructure (while creating local jobs).

Older, fuel oil heated houses will require creative solutions. One example of a typical housing type that needs a creative solution could be the classic “triple-decker” found in Boston and surrounding areas. Originally a way for a family to afford a house because two other renting households helped with the mortgage, triple-deckers have been around for over 100 years. Sometimes applauded, sometimes derided, and sometimes replaced, many have simply survived and still serve three households. Can these structures serve as an example of how to refit older housing with new technology that makes them more comfortable, safer, and less expensive to operate? NEEP would love to be a part of that solution.

NEEP does not have all the answers, but we want to start the conversations. We understand the technologies, we need to study their applications more. We know that financing will be critical, and we know that normal financing channels will not work well for some households and will be very different for rental housing. NEEP knows market transformation, it’s what we do, and we know that building decarbonization will have many moving parts, require effort over a decade or two, and need substantial financial support. It also has huge benefits both globally and locally.

Mostly, if we are serious about decarbonization, we need to start. And the place to start must include low-income, and it must include innovative solutions. This will not be business as usual.

This blog is part of Building Decarb Central, a series of blogs and other resources aimed at providing a constant flow of information on building decarbonization. Be sure to check out our web portal for more stories, resources, and information.