By Andrew Winslow | Thu, July 29, 21

It is no secret that the commercial and industrial sectors use a tremendous amount of energy. In 2019, they accounted for seven percent and 23 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions respectively. This high level of energy usage and carbon emissions represents both a challenge and an opportunity for decarbonization.

On one hand, these sectors include companies and industries with huge facilities and energy intensive processes that devour energy and emit significant amounts of carbon. Big buildings house more equipment to operate, workers to manage, and space to heat and cool. For example, in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic region, the chemical industry uses 173 trillion BTUs (TBTU) of energy, the paper industry uses 120 TBTUs, and the iron and steel 113 TBTUs.

Many assume the high energy consumption is an unavoidable cost; however, this is not always the case. This challenge means there is opportunity for significant energy, carbon, and financial savings from relatively untouched and unstudied sectors when compared to residential buildings. Strategic energy management (SEM) is specifically designed to target these hard-to-reach customers and can play a key role in achieving aggressive state decarbonization goals through low- to no-cost energy efficiency measures and energy management.

Strategic Energy Management is a set of processes that focus on long-term energy planning and energy efficiency improvements to building infrastructure. It requires buy-in from all levels of an organization, from administration to on-the-floor employees. Many program administrators (PAs) offer SEM as a flexible program that provides guidance from experts and opportunities for collaboration with others going through the same process. Facilities set personal targets, identify areas for improvement, set a schedule for making upgrades, and train staff to get support from the whole organization. This is known as a “cohort” model. In the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic region, PAs in Vermont, New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and just recently, Pennsylvania, run SEM programs. The U.S. Department of Energy also offers a self-guided application that boils SEM down into easy-to-digest components called the 50001 Ready Navigator.

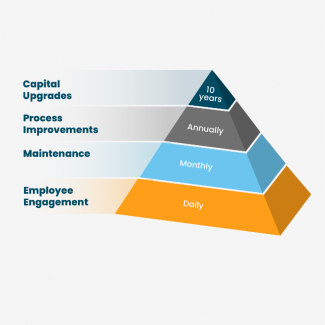

SEM Offers Multi-Layered Savings

Strategic Energy Management is appealing because of its long-term outlook and focus on low- and no-cost, non-capital energy efficiency measures. It has the potential to capture a huge amount of savings without purchasing high efficiency retrofit equipment by instead focusing on three main buckets of non-capital improvements: operations, behavior, and maintenance. A common thread throughout these three different areas of improvement is that there must be continuous effort for energy savings to continue year over year.

Operations savings are derived from modifying equipment parameters to reduce energy consumption without affecting the overall product. This includes actions such as altering the pressure, temperature, flow rate, or speed of equipment. For example, raising a chiller’s water supply temperature or reducing the operating pressure of a compressed air system. These changes reduce energy demand without affecting the end product or investing in new equipment.

Behavior energy improvements involve adjustments to human behavior and habits. This can be as simple as turning off lights and equipment when not in use and as complicated as running fewer redundant systems. NYSERDA’s Potters Industries SEM case study identifies that much of the company’s progress so far is the “result of individuals considering energy use within the scope of what they do and suggesting adjustments.” Staff at all levels can be educated and encouraged to think about their responsibilities, and signage can be put up to remind employees of best practices.

Maintenance improvements refer to adopting maintenance procedures for systems and equipment that take energy performance into consideration. For example, regular maintenance checks can catch energy-draining errors such as leaks and failed steam traps, or frequent cleaning of heat exchangers and air filters to ensure maximum energy performance. Maintenance type improvements will vary greatly by industry.

An economy wide decarbonization study by the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) estimates that the industrial sector has the potential to reduce energy consumption by 33 percent compared to a reference case, but that savings will be more difficult to achieve than for the buildings sector. This assumption may be an underestimate because it does not factor in strategic energy management and deep energy savings in the industrial sector.

A round-up of programs across the United States shows that on average, operation, maintenance, and behavior energy saving measures account for 5.4 percent of annual savings. Capital expenditures can account for another three percent. Assuming growing participation rates, these savings could theoretically achieve reductions of seven terawatt hours in the commercial sector and 24 terawatt hours in the industrial sector by 2030. The Energy Trust of Oregon reports that SEM accounts for 20-25 percent of savings across its C&I programs and The Bonneville Power Administration reports that SEM accounts for 15 percent savings from its program. The most significant variable in SEM potential is the participation rate.

As an example, in 2019 the Okonite Company, an insulated electrical wire and cable manufacturer with a facility in Rhode Island, started on a three-year SEM process supported by National Grid. The cable manufacturing process is incredibly energy intensive and uses approximately 570 times the amount of energy as the average U.S. home. Controls were set to reduce the run time of pre-heaters and dryers and to allow HVAC fans to be controlled by occupancy so rooms that were not being used were not unnecessarily heated or cooled. Signs were also posted to remind employees of energy-saving practices like shutting equipment off when not in use. After one year of participation, the manufacturing plant achieved significant cost savings in the low six figure range. The success of the Rhode Island facility is leading the Okonite Company to implement SEM at its other locations across the country. For a more detailed look at the Okonite Company’s SEM program see NEEP’s recently released case study.

States cannot achieve their increasingly aggressive greenhouse gas reduction goals without reducing energy and emissions from the large commercial and industrial sectors. In many ways, SEM has already proven to be a successful pathway to energy savings in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic. Its unique, whole-building approach that incorporates behavioral change and education with energy efficiency measures is an important strategy to reduce emissions from these buildings with the biggest carbon footprints. But perhaps there are opportunities for SEM to do more.

Benchmarking and building performance standards are policy tools that are becoming increasingly popular to reduce energy and carbon emissions from existing buildings. SEM could work in tandem with these policies as a resource to help large industrial and commercial buildings comply and contribute to decarbonization goals. Benchmarking is the process of recording and reporting annual energy usage to a jurisdiction. An EPA analysis showed that the simple act of reporting energy usage reduces annual energy usage by 2.4 percent because building owners make voluntary data-driven decisions and investments. Since benchmarking is a critical feature of SEM, facilities will have an easy time complying with jurisdictional benchmarking ordinances. Building performance standards (BPS) place limits on energy usage and/or carbon emissions from existing buildings. SEM could be offered as part of a suite of resources for building owners or a backstop for facilities that fail to meet the standard. SEM offers a guided pathway for owners of large buildings that might otherwise not know how to reduce their energy usage.

Later this year, NEEP will publish a report that highlights strategies to scale the adoption of strategic energy management in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic region. The suggested strategies will focus on approaches to complement existing SEM programs.