By Brian Buckley | Wed, October 26, 16

Tucked away at the bottom of page 81 in Con Edison’s recent 120 page settlement agreement lies a sentence that will likely alter the course of energy efficiency programs in the state:

“Electric rates are designed for the Company to recover the costs of the Energy Efficiency Program, system peak reduction program and the equipment portion of the EV Program over ten (10) years, including the overall pre-tax rate of return on such costs.”

This language foreshadows what could be a broader move on behalf of the Public Service Commission (PSC) to include energy efficiency within a utility’s rates — on par with treatment of other energy resources — rather than fund it via a line item surcharge on a customer’s bill. When combined with the PSC’s recent guidance regarding use of outcome-based utility Earnings Adjustment Mechanisms (EAMs), this creates the opportunity for an extensive expansion of energy efficiency programs in the state; an expansion currently under consideration by the state’s Clean Energy Advisory Council.

For background and details on the opportunity for program scale-up in New York, read on…

Energy Efficiency Funding in New York State

Established within a 1996 order of the Public Service Commission, the System Benefit Charge (SBC) has been a major driver of New York’s successful energy efficiency programs, using the primary beneficiaries of energy efficiency programs — the ratepayers — as a stable source of funding. The cost of the program is socialized across ratepayers on a volumetric basis of approximately $0.006/kWh, when most ratepayers pay between $0.15/kWh and $0.18/kWh for their electricity. Such programs have helped New York consistently score near the top of ACEEE’s State Scorecard, due in part to the stability associated with its SBC-funding.

Yet, despite its history of successfully supporting energy efficiency programs, the SBC is a point of contention for some stakeholders who see only a line-item on their bill, rather than understanding the benefits derived from that investment.

Although the SBC charge is less than 1/20 of the average customer’s total bill, that ratio can be much higher for large end-users who pay as little as $0.06/kWh for their overall electric service. In such cases, the SBC represents almost 1/10 of a customer’s overall bill; not an insignificant amount, and an easily identifiable line-item at the bottom of a customer’s bill.

Consequently, in spite of the net benefits provided by the SBC-funded programs, some large energy users have pushed legislatures and utility regulators for the ability to opt-out of energy efficiency programs and the associated SBC collection mechanism. Such opt-outs can be troublesome because those users still derive value from the system and societal benefits provided by other ratepayers who continue to pay into the programs. Within that context, some forward-thinking regulators have been evaluating energy efficiency program funding opportunities outside of the SBC charge.

Making Way for a Reformed Energy Vision

Making Way for a Reformed Energy Vision

Early in the New York PSC’s “Reforming the Energy Vision” proceeding, the Commission outlined its goal of leveraging ratepayer contributions to animate markets for, among other things, energy efficiency (p. 4). The hope was that as more energy efficiency occurs as a result of market animation, the need for funding via the SBC would diminish. Seeking to place energy efficiency on level footing with traditional utility investments, the Commission also suggested that “Instead of funding the proposed programs through a surcharge, they will be recovered through rates as an operating expense,” (p. 73).

Later, in a bit of a course correction, the Commission clarified that “only costs associated with utility personnel working directly on energy efficiency programs should be recovered through base rates,” and the remainder of the program costs would be recovered through a new cost tracker component of the SBC (“EE Tracker”), which would be capped at 2015 spending levels (p. 14). Further, NYSERDA’s portion of the SBC funding is planned to ratchet down over time, providing for less overall energy savings.

Those spending levels would buy New Yorkers annual incremental savings at a little more than one percent of retail sales, far below some of their neighbors in the region who have been able to achieve more than three percent. Furthermore, this figure doesn’t incorporate the projected decline in savings as NYSERDA begins the ratcheting-down their SBC-funded energy efficiency savings.

Yet, in keeping with the goals of the State Energy Plan and recently approved Clean Energy Standard, the state’s efficiency programs would have to reach much higher than one percent. Faced with a declining collection mechanism and private markets support that has yet to materialize, another source of funding would be necessary.

Aiming for Greater Savings: The Con Edison Settlement Agreement

If approved by the PSC, the above-referenced settlement agreement may provide for just such an avenue. In keeping with the Commission’s January order, it proposes that Con Edison procure approximately double the savings that had been proposed via its EE tracker-funded programs and recover the associated funding through rates over a 10-year period. The settlement also allows Con Edison to recover its overall pre-tax rate-of-return on those energy efficiency program investments.

That’s a really big — make that YUGE— deal.

The settlement doesn’t just move funding for energy efficiency into the rates, it also places it on equal footing with other investments in the eyes of utility shareholders. For example, when a utility invests in building distribution infrastructure, such as a substation, regulators grant its shareholders a return on their equity of approximately 8.9 percent, and an overall rate of return on the substation investment of about 6.7 percent. During the years prior to the Commission’s Reforming the Energy Vision proceeding, the utility program administrators were offered performance incentives equivalent to approximately four percent of their efficiency program budgets (p. 98). By recovering program spending from within the rate base, the utility program administrator would receive its overall rate of return — approximately 6.7 percent — for investments not funded by the EE tracker surcharge. Such an incentive also places New York’s utility program administrators on par with their neighbors in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, whose performance incentives amount to between five and seven percent of efficiency program spending (p. 98).

Its also important to note however, that costs associated with amortization and depreciation will raise the overall cost of programs beyond those associated with performance incentives in neighboring states (p. 55-59). For example, an analysis completed by the EPA found that $5 million in efficiency program spending over a five year period with an amortization period of ten years and ten percent return on investment would actually cost ratepayers $7.5 million (p. 56). If that funding were instead collected through a surcharge or rider, rather than allowing the program adminstrator to earn ten percent on the unamortized amount once a year for ten years, it would only cost ratepayers $5.5 million. Following this example, in New York, where the program administrators will earn a rate of return of 6.7 percent and the investments will be amortized over 10 years, the overall costs to ratepayers will be 1/5 more than if funded via a non-bypassable surcharge rather than capitalized and amortized. That said, the language in the settlement agreement is unclear about whether the "overall rate of return" will be provided annually on the unamortized balance, or whether the utility will earn a cummulative rate of return on it's investment equivalent to 6.7 percent over period of ten years.

Carrots, Sticks, and Earnings Adjustment Mechanisms

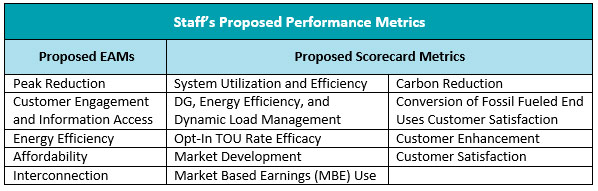

In theory, pure rate-of-return cost recovery for energy efficiency program investments — as practiced, for example, in New Mexico — rewards spending alone, and provides little incentive to efficiently manage the costs of program administration. Recognizing this shortcoming, the Commission staff developed a whitepaper suggesting Earnings Adjustment Mechanisms (EAMs) might be utilized to encourage system-wide policies that promote the public interest, but might not otherwise be incented through simple cost-of-service or revenue regulation (p. 54-65). The EAMs are meant to impact a utility’s overall rate of return, with an initial ceiling of 100 basis points for all new incentives (p. 68). The Commission also suggested that certain metrics be tracked via a scorecard, but have no impact on earnings.

The EAMs as originally proposed in the staff whitepaper are outlined in the table below.

Also of high value to readers may be the New York’s Clean Energy Organizations Collaborative (CEOC)’s comments on the Commission staff whitepaper, which suggested an even broader array of EAMs and scorecard metrics that hint at what regulatory regimes might look like for the utility of the future. (p. 28-9)

While the Commission didn’t mandate the full suite of EAMs suggested by staff or the CEOC, it did suggest some initial EAMs including: (1) load factor; (2) interconnection timelines; and (3) system-wide energy usage intensity. Using these guidelines as a starting point, the Commission asked that each utility propose EAMs within its respective rate case filings.

Energy Efficiency Targets and EAMs Moving Forward

In order to help determine which energy efficiency targets might be used to set baselines for the EAMs, the Commission directed the Clean Energy Advisory Council to publish an options paper recommending metrics and targets for the utilities and Commission to use as a guide.

A first draft of that report was filed last week with the Clean Energy Advisory Council (p. 37-117). If you’re interested in what the report says but don’t have the time to read all 80 pages, you can look ahead to page 117 where a set of 25 slides summarizes its findings. In general, working group stakeholders seem to agree that procurement of energy efficiency beyond the bounds of the current EE tracker funding would be necessary to achieve the state’s energy goals in the least-cost manner, but the strategies for achieving those savings differ.

Whether the Commission agrees with the settling parties in the Con Edison proceeding, as well as the working group recommendations, remains a question for future resolution.