By Ethan Hughes | Fri, August 31, 18

Welcome to the latest REED Rendering issue, a series of blogs where we bring your attention to interesting trends that we see in the data and the stories behind those trends.

Energy efficiency is one of the lowest-cost carbon reduction tools. According to data from NEEP’s Regional Energy Efficiency Database (REED) data, in 2016 the Northeast region was able to avoid over three billion pounds of carbon emissions from improved building energy efficiency – that’s like taking all cars in Pittsburgh off the road for a year – all for a fraction of the price of retail electricity and natural gas. Even with a modest budget, energy efficiency can produce large cuts in carbon emissions, but stable funding mechanisms are critical for energy efficiency programs. Which begs the question, have traditional funding mechanisms for energy efficiency been enough?

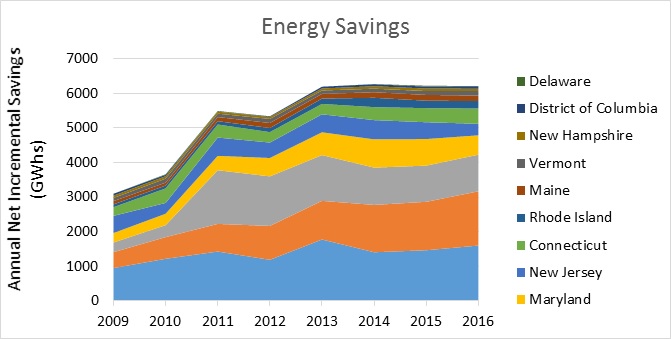

Figure 1- Energy Savings Achieved by Energy Efficiency Programs

Smile for the Snapshot!

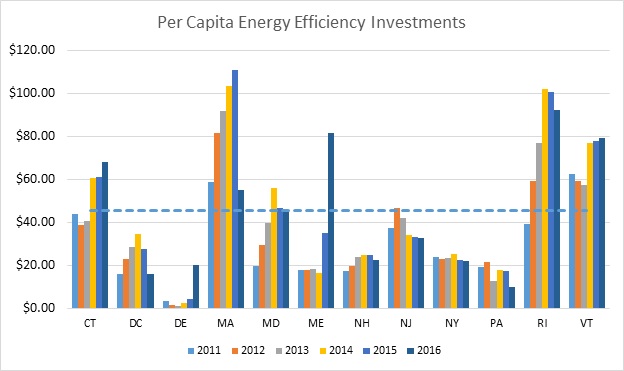

The regional energy efficiency snapshot synthesizes data from REED to generate an overview of energy savings from utility energy efficiency programs. In 2016, the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic region invested, on average, approximately $46 per capita in energy efficiency, totaling a whopping $1.81 billion. But as mentioned in REED Rendering Issue #8, the region saw a decrease in total energy savings – from 4.7 million MWh in 2015 to 4.1 million MWh in 2016. Remember, less energy savings from energy efficiency means less avoided carbon emissions from energy efficiency – one of our most effective least-cost carbon reduction tools.

Figure 2 - Per Capita Energy Efficiency Investments: Electric and Gas Combined

So we’re falling short, but how short?

Most states in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic region share the same long term carbon reduction goal: an 80 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2050 (as compared to early 2000’s emission levels). Currently, we are on track to miss that target. Estimates suggest that despite all the progress we have made in the last decade, we still need to see a 76 percent change to reach our 2050 goals. T-minus 32 years and counting.

Common funding mechanisms

While each state in the region has its own driver(s) for developing energy efficiency policies and funding mechanisms, most programs are often focused on one of two things: (1) creating markets for energy efficient equipment or infrastructure and (2) building capacity to deliver energy efficient goods and services. Most states have decoupled utility revenue from energy sales and implemented energy efficiency resource standards (EERS) thus, removing the incentive to sell high quantities of energy by establishing a certain level of energy savings that must be met. The basis of utility rebates and tax incentives for energy efficiency programs (i.e. free building energy assessments, rebates for energy efficiency improvements and equipment) arise from this policy framework. Utilities fund efficiency improvements by adding a charge onto ratepayer bills. Then, the utility will either directly implement energy efficiency projects using ratepayer money, or place the money into a fund or trust operated by a third party.

The piggy bank

Because the nature of energy efficiency programs to transform the market is complex and happens over time, it is often imperative that programs have multi-year funding. State government budget allocations often lack that multi-year security because energy efficiency budgets are at risk of budget fluctuations through diversion of funds – energy efficiency funding is often moved into general funds where its original intent is lost. Therefore, a diverse portfolio of funding sources is crucial.

Evolution of something new funding mechanisms

The region has seen innovative funding mechanisms for energy efficiency develop in the form of targeted grants and green banks. Targeted grants reduce the risk of diversion as those funds are targeted towards a specific program sector and sometimes implemented by the state energy office or federal government. Maryland Governor Larry Hogan’s two million dollar, three-year grant for energy efficiency investments in commercial manufacturing is a prime example of a successful targeted grant.

The Connecticut Green Bank, the nation’s first green bank, uses a variety of loan programs to help spur investment in energy efficiency projects and clean energy solutions. Connecticut Green Bank has a replicable three-part organizational structure: an investment division responsible for attracting capital to finance green policy goals, a program and marketing division responsible for deploying capital for financing, and a corporate division that provides administrative support. Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank (RIIB) saw inspiration in Connecticut Green Bank’s success and developed the Efficient Building Fund (EBF), which has deployed over $17.2 million towards municipal-building energy upgrades.

Innovative funding mechanisms for energy efficiency are still in their infancy and continue to evolve. Yet, while these mechanisms hold great promise for efficiency funding, it is hard not to wonder if they will be enough to help meet our carbon reduction goals. We should consider what is driving all of our current funding mechanisms: is it carbon reduction, or just energy savings?

Who’s behind the wheel?

The long-term carbon reduction goals have always been about reducing carbon emissions, not energy savings. As they should be: excess carbon emissions are dilapidating ecosystems, ravaging human health, and changing our global climate on an unprecedented scale. Yet, most funding mechanisms for energy efficiency revolve around energy savings first and foremost, largely because of the importance placed on energy savings by EERS and utility metrics – most utilities with EERS track progress in kWh savings. In order to drive energy efficiency growth for the purpose of meeting our carbon reduction goals, these policies and metrics may need to shift focus and center on carbon reduction primarily (i.e. carbon pricing, and cap and trade). Some utilities have begun including metrics that better represent carbon reduction, like Nation Grid’s 80x50 pathway. Also, carbon-reduction-centric policies like the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) continue to expand as New Jersey rejoins and funding is extended to 2030. Whether these strategies will give us a better shot at reaching our carbon reduction goals remains to be seen. But one thing is for certain, funding for energy efficiency needs to expand, as efficiency has a huge role to play in not only achieving energy savings, but carbon reduction.