By Brian Buckley | Thu, October 29, 15

UPDATE: On January 25, 2016, the Supreme Court voted to reverse and remand the lower court's decision, reaffirming FERC's jurisdiction over compensation levels for demand response in wholesale markets.

It’s not every day that the U.S. Supreme Court contemplates the boundaries of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)’s authority under the Federal Power Act, but that’s exactly the heart of the matter heard before the Court earlier this month in FERC v. Electric Power Supply Association (et al.). You can listen to this month’s oral arguments here. The post below provides a brief summary of Order 745, outlines the case before the Court, and details the potential impacts on energy efficiency. May it please the court…

FERC’s Order 745

Issued in 2011, Order 745 set the rules for participation of demand response in wholesale energy markets, setting compensation at the same locational marginal price that’s available for supply resources. FERC issued the Order in response to a directive by Congress under the Energy Policy Act of 2005 prescribing that “unnecessary barriers to demand response participation in energy, capacity, and ancillary service markets shall be eliminated.” Congress issued this directive because of an increasing awareness that the most expensive MWh for our transmission and distribution grids are those needed during the seasonal peaks.

Just how expensive are those peaks?

The New York State Department of Public Service estimates that if the 100 hours of greatest peak demand were flattened, long term avoided capacity and energy savings would range between $1.2 billion and $1.7 billion per year. In neighboring PJM, demand response is estimated to have saved electricity users $11.8 billion through wholesale market participation in 2013 alone.

So, what does this have to do with the Supreme Court?

FERC v. EPSA

In May 2014, the District of Columbia Court of Appeals vacated Order 745, casting a shadow of uncertainty around the future of demand response. The case before the Supreme Court is built around the two issues within the lower court case, which are described in brief below:

- Jurisdictional: Does the Federal Power Act grant the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission the authority to regulate the rules operators of wholesale energy markets use to pay for reduction in electricity consumption?

- Procedural: Did the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit err in holding that the rule was arbitrary and capricious?

Jurisdictional Issues

Under the cooperative federalism model set forth in the Federal Power Act, jurisdiction over retail rate-setting is generally delegated to the states, and jurisdiction over wholesale rate-setting (sale for resale) is generally delegated to the federal government (FERC). In the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, the rate-setting rules promulgated by FERC affect markets run by three independent system operators: PJM, ISO-NE, and NY-ISO.

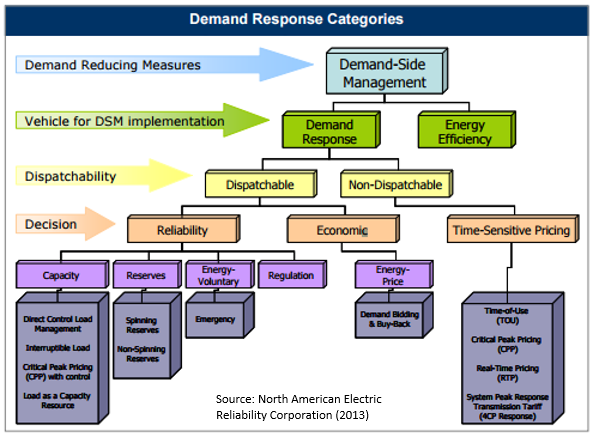

These organizations oversee wholesale markets for energy, capacity, and ancillary services (spinning reserves, frequency regulation, voltage support, etc. - see table below). Order 745 set the compensation level of demand response resources in the energy markets at the same level offered for supply resources, locational marginal pricing, so long as the demand response resource passes a “net benefits” test.

In a move that surprised some, the D.C. Court of Appeals saw this action — setting the price offered in exchange for a commitment not to use power — as an overreach beyond FERCs authority to regulate wholesale energy market transactions, instead characterizing it as retail rate-setting, a domain reserved for state utility commissions. While the lower court’s ruling was specific to markets for energy only, the same reasoning used by the court would likely apply to capacity markets. Shortly after the ruling, First energy filed a complaint with FERC seeking to disqualify participation of demand response in the capacity market. The complaint remains pending.

Why was the court’s decision surprising?

As a matter of public policy, the courts generally defer to an agency’s rule promulgations under the reasoning that agencies possess a level of resources and subject matter expertise exceeding that which is available to the courts. Perhaps the best-known annunciation of this principle is within the case Chevron v. NRDC, which outlines a two-step test (colloquially known as the “Chevron two-step”) for determining whether a court should defer to an agency action.

First, the court asks whether the enabling statute is clear, or ambiguous on the matter. In the present case, many would argue that the statute is ambiguous on the matter of whether demand response should be characterized as a wholesale or retail transaction. This is largely because demand response didn’t exist in 1920 when the Federal Power Act was enacted, but also because the language within the Energy Policy Act of 2005 amending the Federal Power Act does not directly address whether such transactions are either wholesale or retail transactions. If the statute is found to be ambiguous on the matter at hand — which the lower court did not — then the courts then move to step two of the Chevron test.

Procedural Issues

In step two of the Chevron test, the courts contemplate whether the agency’s interpretation of the statute was reasonable. In the present case, the lower court ruled that FERC did not act reasonably in determining the compensation for demand response, instead finding their actions to be “arbitrary and capricious” under the Administrative Procedure Act.

This finding is based on FERC’s response to an argument that demand response should be compensated at the locational marginal price, minus the cost of forgone electricity, rather than the simple locational marginal price as proposed in Order 745. FERC’s response stated that demand response resources are comparable to that of generation and should therefore receive the same level of compensation; a response the Court of Appeals characterized as “talk[ing] around the arguments” rather the “direct response” required by the Administrative Procedure Act.

Whether the Supreme Court will side with the lower court on FERC’s authority, procedural grounds, or both is unclear. Yet, curtailment service providers, regional transmission organizations, and others are already beginning to react. For example, PJM Interconnection released a whitepaper in October 2014 outlining a path forward after the Court of Appeals decision. Amongst other things, the whitepaper anticipates that the court’s reasoning will be applied to capacity markets as well, but also suggests a solution: curtailment service providers work through load serving entities, namely utilities, to incorporate demand response into their bids for required capacity.

What does all of this mean for energy efficiency program administrators?

Why FERC v. EPSA Matters for Energy Efficiency

The case before the court is important for energy efficiency programs because an affirmation of the lower court’s decision will likely affect energy and capacity pricing and avoided costs, and may reinforce a trend within the industry toward the partnership of utilities and demand curtailment service providers.

A ruling that characterizes demand response as a retail transaction, limiting its ability to participate in wholesale energy and capacity markets will likely raise the MWh cost of electricity. Further, such a ruling might require near-term infrastructure buildout to fulfill the capacity needs that demand response had been planned to displace. Throughout the region, capacity auctions take place several years ahead of when that installed capacity is needed, and demand response has already bid into several wholesale capacity auctions until 2018. Removing the capacity provided by demand response resources will result in acquisition of more expensive supply resource capacity.

Increases in both wholesale energy and capacity related costs will lead to higher electric rates for customers. In turn, incorporation of higher avoided costs into energy efficiency cost-effectiveness screening tests might allowing program administrators to reach deeper for energy efficiency savings. On the other hand, higher retail electric prices might be construed by some as a reason to limit investment in energy efficiency, which often appears on a customer’s bill as a line-item.

Such a ruling might also inadvertently have the effect of accelerating a trend toward integration of state level energy efficiency and demand response programs. The flexiwatt, as the Rocky Mountain Institute has coined it, is beginning to appear in energy efficiency programs throughout the region as policy makers push for reduction of costly peak MW usage. A few examples are listed below:

Massachusetts’s draft 2016-2018 efficiency program plans include national grid’s projected acquisition of more than 50MW of demand response in 2018 (see table, right)

Massachusetts’s draft 2016-2018 efficiency program plans include national grid’s projected acquisition of more than 50MW of demand response in 2018 (see table, right)- Connecticut's draft 2016-18 efficiency program plans include commitments to demand response programs and pilots.

- Earlier this summer, the New York Public Service Commission issued their Order Adopting a Dynamic Load Management framework, and demand response featured prominently as a resource meant to avoid infrastructure buildout in the Brooklyn Queens Demand Management project.

- The Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission reauthorized demand response programs for Phase III of the Act 129’s Energy Efficiency and Conservation Programs, which had previously been removed from the program

- Maryland’s Empower program boasts more than half a million connected devices that the state’s utilities use for direct load control, with demand response accounting for almost a third of the program’s spending.

These programs present an opportunity for energy efficiency program administrators to find synergies with between energy efficiency and demand response offerings.

Until recently, demand response has been less cost-effective than peak coincident energy efficiency investments due to the limited duration of their impact. But two things have changed in the last decade or so. First, policies promoting energy efficiency as a first order resource have kept annual electric loads flat in many regions of the United States, but been less successful at curbing the growth of peak load. Second, we’re beginning to see a proliferation of connected devices and advanced lighting controls which offer opportunities for savings via both energy efficiency and demand response. At the same time, we’re seeing distribution utilities partner with third parties to engage customers around demand response, particularly in the area of behavioral programs. These developments are making demand response a more appealing investment.

What Happens Next?

Is it possible that a Supreme Court ruling in favor of electric power generators has the effect of sending curtailment responsibilities through utilities, encouraging integration of demand side management solutions under the umbrella of efficiency program administrators? Or alternatively, will a reversal of the Court of Appeals decision reinstate Order 745 and provide FERC with solid legal footing on it authority over demand response? With a decision not likely until early 2016, we will have to wait and see.